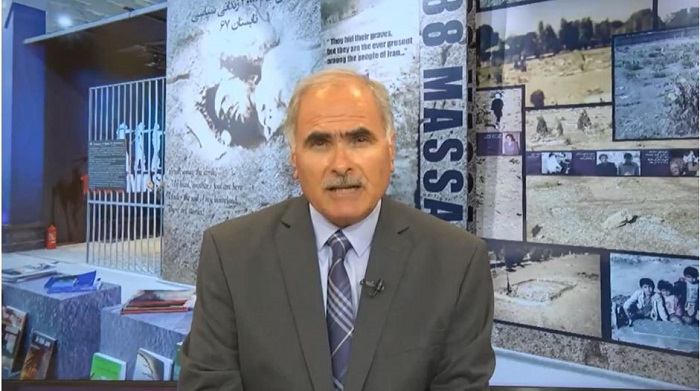

The 1988 massacre of 30,000 political prisoners, most of whom were affiliated with the main Iranian opposition movement, The People’s Mujahedin of Iran (PMOI / MEK Iran).

Eyewitness Hossein Farsi

My name is Hossein Farsi. I was a political prisoner from 1981 to 1993. I was held in Evin, Ghezelhesar, and Gohardasht prisons. I was arrested on charges of supporting the Mojahedin-e-Khalq, MEK, and conducting political activities with respect to the MEK.

In 1988, when the massacre happened, I was in Gohardasht Prison and spent four days in and around the Death Committee and the Death Corridor. In order to make clear how this massacre happened and that it didn’t just take place overnight, please allow me to go back so I can give a more detailed account.

Since early 1986, two years before the massacre, tensions were rising between the prisoners and the wardens. The warden constantly carried out suppression and the prisoners resisted with high morale. The resistance happened in various forms, from hunger strikes to refusing visits, among other acts.

One of the sources of tension between the warden and the prisoner was the issue of what the prisoners’ charge was said to be. This meant that prisoners who supported the MEK couldn’t use the word “Mojahed” to describe their charge or the term “Mojahedin.” They were asked to use the Khomeini-made term “Monafeqin.”

We were supporters of the Mojahedin

From 1987, a year before the massacre, this war had started between the prisoners and the regime. And we were insistent that we were supporters of the Mojahedin. They would severely torture prisoners. They tortured anyone who used the word “Mojahedin,” with the goal of forcing them to back down from using that term.

Several months before the massacre, some transfers and relocations took place. In particular, in Gohardasht prison, based on the positions undertaken by the prisoners, the prisoners were categorized into groups. I myself was transferred to Gohardasht in early 1988. One of the gruesome scenes that happened in Gohardasht and I should point out here was the way we entered the prison.

We were taken to Gohardasht in February 1988. It was night. And it was really cold. We were blindfolded and handcuffed on the bus. When we got off the bus, they removed our handcuffs but left the blindfolds. As soon as we moved, we noticed that they had created a “tunnel” made up of 50-60 IRGC guards lined up on each side. As we walked between the two rows, they would hit us with sticks, batons, cables, chains, and whatever they were equipped with. After going through this, we were taken to the third floor. It was an empty ward and it was extremely cold.

There, they ordered us to remove all our clothing. There were 180 to 190 of us. We resisted. They beat us severely to take off our clothing by force. And even after, the IRGC guards struck the naked bodies with cables, sticks, iron bars, and anything they had in their hands. They were incredibly violent. It was a gruesome and painful experience. One of the people who commanded the others and was present at the scene was an IRGC personnel named Hamid Noury. Another one was the deputy head of Gohardasht Prison named Davoud Lashkari.

Categorized prisoners based on their political

This stage passed. They had categorized prisoners based on their political positions. We were in a ward where the common denominator among all of us was that we had all been freed before but arrested again. This tension continued until July.

By the end of July, we noticed an abnormal situation. The state-run newspapers that we used to receive every day, like Keyhan, Ettelaat, and Jomhouri Eslami, were no longer delivered. We were also allowed to go into the prison yard for an hour every day. But that was also suspended.

We used to buy basic necessities from the prison shop. But that shop was suddenly closed.

We did not have a television set. But the wards beside us did. We communicated through Morse Code with them and found out that their TV sets were taken away. We noticed that the situation is becoming highly unusual.

On July 29 at night, they called us and asked questions from each of us. They asked about our charges. Unlike the previous days, when we responded that our charge was supporting the “Mojahedin,” they did not react angrily or resort to violence. At times, they would ask: Do you want to be pardoned?

We were sitting there blindfolded

We returned to the ward and felt that the situation is unusual. Their conduct was strange. But we never imagined the things that would happen in the following days.

On July 30, in the morning, they called us and they took us out of the ward in a hurry. We were blindfolded and taken to a three-story administration building of the prison. In the middle was the visiting hall. The lower floor was an office area where the prosecutor’s office for prison supervision was located. We were sitting there blindfolded.

I saw an unusual thing, which was very weird and unique. Two IRGC guards with Uzi machine guns were seated by the door. This was very weird. Guns were banned from inside the prison. After a few hours, I was called into the room. When I removed my blindfold in the room, I saw two mullahs and a person in plainclothes.

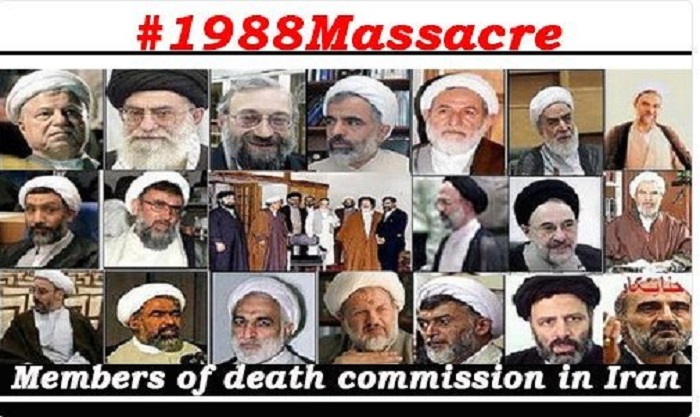

The person in plainclothes there was Morteza Eshraqi, the Tehran Revolutionary Prosecutor. The mullah in the middle was Hossein-Ali Nayyeri, who is currently one of the judges of the Supreme Court. Sitting beside Nayyeri was a young mullah whom I did not recognize at the time. He was Mostafa Pourmohammadi, who was one of the officials of the Intelligence Ministry and a member of the Death Committee. Later on, he became the regime’s Minister of Justice and Minister of Interior.

These were members of the Death Committee. All three had to sign the death sentence. After questions about the prisoners’ identity, they asked what are you charged with? Anyone who responded by saying that they were charged with supporting the MEK, their death sentence was signed and nothing else was asked.

The criteria for the Death Committee

The criteria for the Death Committee, as Khomeini had written in his fatwa was that any MEK supporters insisting on their stance are considered Mohareb or “enemy of God” and they must be executed. So, the criterion of the Death Committee was to ask are the prisoners insisting on their stance or not.

Using the term “Mojahedin” means that they are still insistent on their position and still accept all of the MEK’s political and ideological positions. And that is why they were sentenced to death. Just to make it clear how the criterion was in fact the simple use of the term Mojahedin, I want to mention an extraordinary example.

We had a friend who was not arrested for supporting the MEK. There was a group called Arman-e Mostazafin. None of the members of the group, or its leadership, were executed. They were in prison for several years and then freed. This particular prisoner was Majid Pour Ramezan and was from the city of Shiraz.

Amidst this massacre, before he was taken to the Death Committee, when they asked him what his charge is, even though he was originally charged with supporting Arman-e Mostazafin, he said he is a supporter of the MEK. So, they took him, just like our other friends, in front of the Death Committee.

The Death Corridor

There, they asked him what his charge is. He said I am a supporter of the MEK. When they took him to the Death Corridor, they talked to him several times and asked him wasn’t your charge supporting Arman-e Mostazafin? He said, yes originally, but now I am a supporter of the Mojahedin, MEK.

Simply because of using the term “Mojahedin,” he was executed. So, this is the extent to which the criterion for execution was supporting the Mojahedin and defending the positions of the MEK, which was defending the ideal of freedom for the people. This was the only criterion, and not anything else.

I personally witnessed that on July 30, August 12, and August 13, when group after group of prisoner names were read out, and they were lined up in the middle of the Death Corridor, with blindfolds. They were taken to the area of the executions, which was a large hall at the end of Gohardasht Prison and it was called Hosseynieh.

The entire crime was based on a fatwa issued by Khomeini and his serious war against the MEK. In reality, Khomeini resorted to genocide and a crime that was unprecedented in Iran’s history. In the Death Corridor and in those scenes, many things happened. But what has stayed with me is the high spirit and morale of the friends who left and became martyrs. Among them was Hossein Niakan who was my cellmate for several years.

Executions were going on

On August 13, Hossein Niakan was sitting in front of me. While we all knew that the executions were going on, Hossein was singing the Freedom Anthem and was in good spirits. He was smiling and repeating “O’ Freedom after we are gone, shine your light on our graves.”

My other friend, Dariush Hanifeh Pour Ziba, was sitting beside me. He was reciting poems and singing inspirational songs.

The most beautiful thing that Dariush said that day was a poem, which ended with the following words:

O’ morning of freedom

If your Sun needs to feed on a sea of blood

If your spring and gardens blossom out of the wounds on our corpses

And if the anthem of peace and freedom should echo from our blood-drenched cries

We welcome your steps on our warmblood any time

Come, our hearts are the carpet on your path

I want to say that it was with this spirit and attitude that these heroes persisted in their ideal for pursuing people’s freedom and they heroically accepted to be hanged while they said no to the enemy and to Khomeini.

MEK Iran (follow us on Twitter and Facebook)

and People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran – MEK IRAN – YouTube