With Iran’s fraudulent presidential election now over a month away, a campaign to boycott the election is gaining traction across the nation. In recent weeks, Iranian state media outlets have noted the bleak outlook for voter turnout, with the daily newspaper Sharq reporting that even the “most optimistic estimates” indicate a participation rate of 40 to 60 percent. On the same day, another newspaper, Mostaghel, announced that “without a doubt, 37 percent of eligible voters will not participate.”

If these projections turn to be accurate, the Iranian regime may set a new low participation rate, surpassing the previous low set by parliamentary elections in February of last year. But, more significantly, there are no genuine elections in Iran, and all of the candidates are insiders whose entire careers are predicated on fealty to the theocratic regime and the supreme leader.

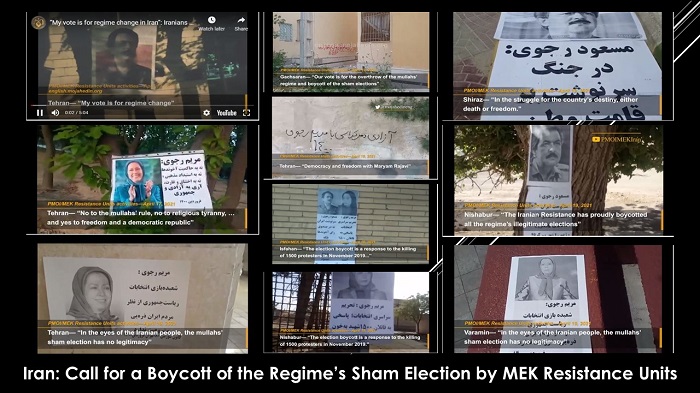

This is the driving force behind the boycott campaign, which is headed by the People’s Mujahedin of Iran (PMOI / MEK Iran) and Iranian society’s “Resistance units,” as it has been in previous years.

In April alone, these protesting groups held protests in at least 250 cities, as well as posting messages in public spaces urging people to boycott elections as a way of “voting for regime change.” As the nation approaches the final stretch before the fake election, these measures show no signs of slowing down.

Furthermore, dissatisfaction with Rouhani’s eight-year administration seems to have intensified the public’s acceptance of the protest movement, as evidenced by multiple gatherings over the past few weeks. Pensioners, whose income is no longer sufficient to pay for life’s most basic needs, have staged more than a dozen of their own protests.

As public support for an electoral boycott rise, so does the regime’s concern that it will lead to more violence for Iranian activists, similar to what occurred in the two years leading up to the parliamentary elections and the Covid-19 Outbreak.

The state-run newspaper Hamdeli sent an alert to all presidential candidates on April 25. “Before we worry about the political consequences of low voter turnout, we should worry about the social consequences,” the article stated, before continuing on to examine the November 2019 uprising and its implications.

In a speech marking the start of the Iranian calendar year in March, Maryam Rajavi, the President-elect of The National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI), recalled that legacy. The Resistance leader predicted that “the fire of the uprisings” will arise from “the ashes of the coronavirus,” addressing recent major clashes between protesters and security forces, especially in Sistan and Baluchistan Province.

Mrs. Rajavi’s portrait has appeared alongside messages calling for an election boycott in cities across Iran. In this way, members of the movement have been reminded that once they “vote for regime change,” a transitional government would be able to take the place of a government whose twin factions currently give no chance of changing policies that have hurt the Iranian people in many ways for more than 40 years.

MEK Iran (follow us on Twitter and Facebook)

and People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran – MEK IRAN – YouTube